...and God help you if you use voice-over in your work, my friends. God help you. That's flaccid, sloppy writing. Any idiot can write a voice-over narration to explain the thoughts of a character-Robert McKee, Adaptation (2002)

Tangled, Disney's adaptation of the Rapunzel fairy-tale, may well have been a good movie, but I gave up after the first 15 minutes - a 15 minutes that included a sardonic voice-over, doing away with all subtlety and forcing plot-establishment down our throats. The movie opened with narration by the movie's male protagonist, Eugene, explaining the setting for the Rapunzel story and the movie's main conflict with broad strokes of self-aware post-modernism, explicitly identifying the films main villain and plot MacGuffin.

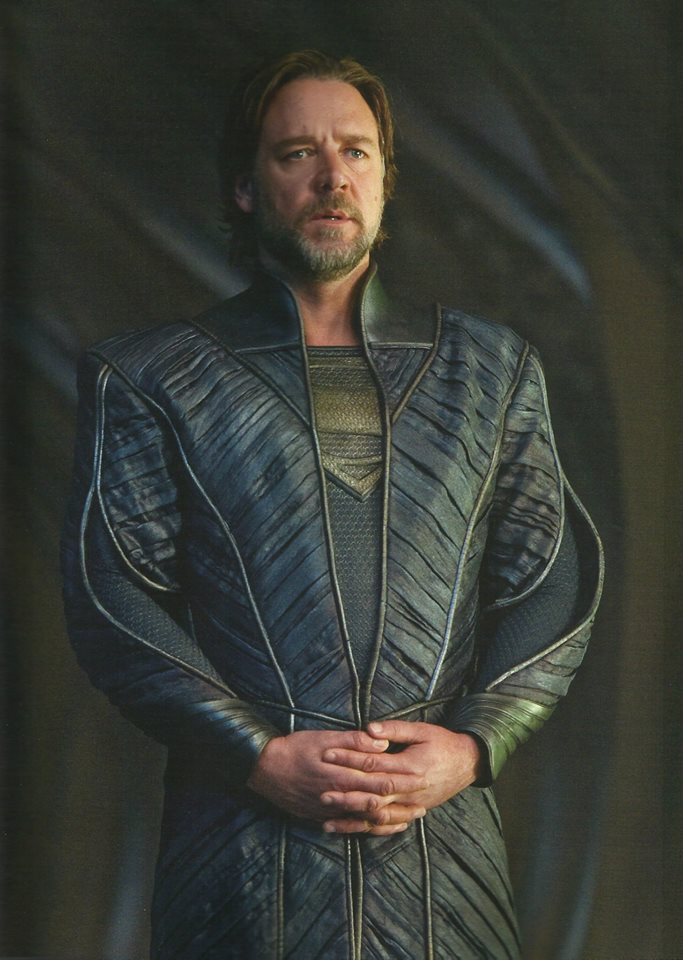

|

| Eugene the vain and Rapunzel the innocent - Tangled (2010) |

The above quote from Brain Cox's character in Adaptation by Spike Jonze and Charlie Kaufman summarises why I found Tangled's voice-over so ham-fisted and uninspiring. These types of voice-overs violate the golden rule of storytelling - show, do not tell. In any medium, stage, written or visual, the story should be shown to us through the setting and portrayal of scenes and characters. Doing this in such a way that the audience doesn't have to think too much (and yet still fully comprehend) involves a high level of skill that comes hand-in-hand with good writing.

The recent trend toward voice-overs by animated films is a never-ending source of frustration for me. In a night of childish nostalgia, I watched Lilo & Stitch (2002), and Tangled (2010) back to back. The stark contrast between the first 15 minutes of both movies seemed to indicate a degeneration in Disney's storytelling technique. Lilo & Stitch relied on visual cues. The body-language, character and set designs suggested volumes about the universe in which Stitch existed and the circumstances behind his incarceration. Key scenes revealed most of the characterisation that we needed to understand Lilo and Stitch as outsiders in their own contexts.

|

| Stitch's initial character design made him seem unruly and frightening |

Tangled explicitly narrated almost everything. It pointed out to us who the villain was, why she was obsessed with eternal youth and exactly how the power of eternal youth was linked with Rapunzel's hair. It also went as far as to point out to us the significance of the 'floating lights' that appear every year on Rapnuzel's birthday. It didn't let us figure out for ourselves what was going on.

The argument that is frequently made to me in favour of Disney movies using this technique is that it gives the film a 'story telling' feel. Whilst I agree somewhat with this sentiment, film makers are given the freedom of a 90-minute long continuous visual medium in order to tell a story - beyond the limits of a 20 page children's picture book. And aside from treating children as bereft of subtlety, voice-overs remove the impact of audiences forming their own emotions as to what is going on. The triumph of Lilo & Stitch is that their characterisation is indirect such that the audience is able to pick out what key facet of their character connects the most. If you tell the audience how they should feel about someone, that sense of having an individual unique bond is lost.

Not every movie or play with narration is bad. Sticking with the Disney/Pixar/Dreamworks theme, Wreck-It Ralph and How to Train Your Dragon miss-step a little with their narration, but it doesn't go into the 'all revealing' territory that many recent movies have. Adaptation plays with this trope in Kaufman's stylistically post modern way. Film noir manages to feature voice-over narration as key technique whilst maintaining storytelling integrity, as in Orson Wells' The Third Man and Frank Miller's Sin City. In these cases, narration is obtuse enough as to let the audience come to their own meaningful conclusions.

|

| Sin City - narration obtuse enough to not compromise subtlety. |

I'm guilty of falling into the voice-over trap myself. Some draft screenplays and stories that I've written have included lots of internal monologue because I was too lazy or tired to figure out another way to show what the character is thinking. But with revision I normally manage to find a more subtle way to show what's going on. And more to the point - writing like this leaves the work open for interpretation, which I find to be the overriding joy of absorbing and discussing literature with my friends.

Show, don't tell.